PHASE II. ALEXANDRIA

12 BCE – 1878

The obelisk was moved from Heliopolis to Alexandria between the 12 and 10 BCE. The significance that the obelisks acquire during Roman time is to be contextualized within the Roman emperors’ fascination with these monuments, many of which were transported to Rome.

This phase of the life of the obelisk is perhaps one of the most fascinating, for the physical and ideological transformations that the two Heliopolis obelisks undergo at this time is at the inception of the Roman and later 18th colonial perception of the Obelisk as a mobile symbol of power. This symbolism is extensively embodied by the crabs, which provide an invaluable documentation of how this process took place. Although both pharaohs left their mark on the obelisks in the form of praising inscription, we only know about the Roman history of the obelisk thanks to the two remaining bronze crabs placed at its base. The crabs not only shed light on this phase of the monument’s history, but also provide an eloquent example of the intersection of the declining pharaonic kingdom and the upraising splendor of the Roman Caesar. Therefore, the analysis of the two crabs and of their inscription, along with the study of the obelisk’s history, may provide interesting insight on the Roman rule of Alexandria and the development of the cult of Augustus in Egypt.

The Crabs of “Cleopatra’s Needle”

Why did the Romans choose to place such animals at the corners of the obelisks? Could the crab be associated with worship of Apollo, the Roman Sun god, and thus could there be a deeper meaning suggested; was the crab chosen by the Romans as an echo of the Egyptian cult of sun god Ra?

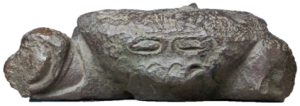

Fig. 1 and 2. On the left: crab 81.2.1 and on the right: crab 81.2.2.

Click on the images to be redirected to the Met’s collection website.

Fig. 3. Obelisk in situ after clearing the debris.

The two crabs were first discovered in 1878, when the 38-year-old engineer Gorringe was appointed by William Vanderbilt to transport the remaining Cleopatra’s Needle to New York City. Until then the two obelisks were thought to be connected to the queen Cleopatra, primarily because the writings of Abd al-Latif, a twelfth-century Arab physician; however, after the discovery of the crabs the obelisks’ history, the Augustan phase was revealed, proving the name to be erroneous.

As Gorringe was removing the debris accumulated at the base of the obelisk, he exposed the 50-ton pedestal for support and crab-shaped bronze wedges placed under two of one of the obelisk’s corners. After an analysis of the bronze wedges, it was soon revealed that they had put in place by the Romans to secure it to the pedestal upon moving it to Alexandria. The two crabs secured the obelisk to the base by the use of bolts and molten metal. This image shows the obelisk in situ, after the debris was cleared away and the irregular broken corners and the two crabs were revealed for the first time in modern time. These bronze wedges, high 37cm and wide 64.5, are realistically shaped as sea-crabs, and depict the crustacean in an advancing position with the claws separated in order to hold the corner of the obelisk. Such a naturalistic articulation presupposed a firsthand observation of a live specimen of sea-crab.

It is broadly accepted that originally there were eight crabs, one sustaining each corner of the two obelisks, yet only two survived, as the others were probably stolen for their elegant manufacture and demanded material. The remaining two crabs were transported along with the obelisk to New York City and donated by Gorringe to the Metropolitan Museum collection in 1881. Today the crabs are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the great hall of the Temple of Dendur, often passed unnoticed by most visitors of the Egyptian galleries. However, these two bronze sea-crabs are essential to our understanding of the history of the two obelisks called “Cleopatra’s Needles.

Translating the Inscriptions

In 1883 the Metropolitan Museum asked Professor Augustus C. Merriam, head of the Greek department at Columbia College, to analyze the inscriptions discovered on one of the crabs’ claws. As visible respectively in Fig.1 and 2, the two crabs are partially damaged, one (81.2.1) completely missing the claws, while the other (81.2.2) having only one claw left. The surviving claw has two original inscriptions on the thick part of the claw, one in Greek on its outer side, and one in Latin on its inner side. The analysis of these two inscriptions, initially performed by Merriam and following by Hall, revealed the names of the Roman prefect, the architect, and the emperor who arranged its transfer to Alexandria, as well as the exact year it took place.

Fig. 4. On the top on both sides is the crab 81.2.2. with its preserved claw, and on the bottom 81.2.1, the amputated crab.

The Greek inscription opens with “L” in a Latin character, which Merriam identified as a derivation from aukabas (ΑΥΚΑΒΑΣ) , a way of indicating “year” typical of Ptolemaic time and used up to the Roman period. The L followed by ē kaisaros (Η ΚΑΙΣΑΡΟΣ) stands for etous ofaoou kaisaros (ΕΤΟΥΣ ΟΦΑΟΟΥ ΚΑΙΣΑΡΟΣ), which means “in the eighth year of Caesar.” The word kaisaros (ΚΑΙΣΑΡΟΣ) clearly refers to Augustus, as he is the only emperor after Caesar –with only a few exceptions— who doesn’t specify his name. As Alexandria was captured on August 1st, 30 B.C, the inscriptions probably refer to 22-23 BC; supporting evidence are the dates of Barbarus’ prefecture, which falls between 20 BC and 14 AD. The arkitekton (ΑΡXΙΤΕΚΤΟΝ), on the other hand, relates to supervisor of transportation of huge masses of stone, as confirmed by Herodotus who also uses this term when describing the transportation of an enormous monolithic chapel from Elephantine to Sais in the time of Amasis. This suggests that transporting enormous worked stones is not a novelty and the Roman were accustomed. The obelisks were, in fact, moved from their original location in Heliopolis to Alexandria during the Roman rule. Therefore, the Greek translation of the inscription is “In the year 18 of Caesar Barbarus set [it] up, the architect being Pontius” (Fig. 5 and 6), while the Latin one is “In the year 18 of Caesar, Barbarus Praefect of Egypt set [it] up, Pontius being architect” (Fig. 7).^1

Fig. 5. Greek inscription on the outer part of the claw of one of the two crabs.

Fig. 6. “In the year 18 of Caesar Barbarus set [it] up, the architect being Pontius.

Fig. 7. “In the year 18 of Caesar, Barbarus Praefect of Egypt set [it] up, Pontius being architect.”

The inscriptions, therefore, prove that the second erection of the obelisk was actually eight years after the death of Queen Cleopatra and that the epithet “Cleopatra’s Needles” is thus erroneous. The inscription thus exposes the administrative history of Egypt during the Roman imperial rule, as well as the power dynamic and iconography adopted by the Caesar at Alexandria. By analyzing Pontius career one can detect how gradually, during the early phase of the Roman occupation of Egypt, diplomatic and professional advancement is tied with the emergence of the fame of the Obelisk. Through Merriam’s analysis of the career of the architect Pontius, one can retrace his birth back to Athens, the beginning of his career in Alexandria, and finally his rise to fame determined especially by the successful transfer of the obelisks from Heliopolis to Alexandria. Merriam writes that “the fame of his success in achieving this difficult task in 13-12 BC (the first of the kind under the Romans), was carried to Rome, and the emperor was induced to attempt the still more difficult feat of transporting two more obelisks to the Capitol.”^2 This analysis thus provides important insight on the use and significance of obelisks during the Roman time, starting from its earliest days under emperor Augustus.

Pliny the Elder expresses the awe generated by the difficulty surpassed in conveying the monoliths to Rome by sea (Naturalis Historia, 36:14). Moldenke, on the other hand, interprets this awe as a Roman jealousy of the great achievements of the Pharaohs and an ardent desire to not only transport these Pharaonic obelisks in Rome, but also manipulate existing ones as well as making their own. The Obelisk, thus, starting from Cleopatra’s Needles, assumes a very important role in the power propaganda of imperial Rome. The crabs prove, therefore, as invaluable documents, as they provide an understanding of the history of Cleopatra’s Needles, specifically their fate after the transfer to Alexandria, and some insight in the administrative world of Roman Alexandria, disclosing the use of obelisks within imperial Rome, starting from this earliest case under emperor Augustus.

But why a crab?

In addition to their political implications, the crabs also shed light on imperial artistic iconography, or rather open an interrogative on the iconography of the crab during Augustan time. During this time the emblem of the crab is frequently found, especially on coins and monuments, and its presence has often intrigued scholars, who in most cases have purposefully avoided explaining it. From a practical standpoint, in the specific case of our obelisks the crabs’ shape fits very well their purpose. Similarly, the figure of the crab might have been chosen given the intrinsic irony of this creature. To place for support a creature that naturally moves backwards might, in fact, construct an intricate play on the concepts of mobility and stability. Could the crab have thus been chosen ultimately as a mocking of the apparent Pharaonic sense of stability overturned by the Roman ingenuity? Other scholars, such as Warren, wrote that the crab is a form adopted not only for its fitting shape or its articulated ornamental feature, but for reasons of deeper significance tied with imperial iconography. What is, thus, the deeper iconographic significance held by the crab? No consensus has been reached, yet two hypothesis relate, on one hand, to the connection between two separate symbols of the sun, the first being the obelisk as a representation of Ammon-Re, and the second being the crab, when associated to Apollo and thus to the sun. On the other hand, the second hypothesis has its base in the apotropaic virtue of the crab, and thus inserts it within a distinct Hellenistic tradition of talismanic usage.

The sun symbolism

Going back to an iconographic interpretation, the “sun symbolism” hypothesis is based strongly on the supposition that the prefect Barbarus and the architect Pontius, or whoever was responsible for the choice of the crab iconography, had a deep knowledge on the correspondences between Roman and Egyptian mythology, and was conscious of the political implications generated by certain analogies. Firstly, the political and religious significance of the obelisk must be validated. Moldenke writes that obelisks represented “life in the sunshine of glory,” and were erected in honor of the sun in all of its phases, in opposition to the pyramids that symbolized the sun after it had set. Once this connection between the obelisk and the cosmology and mythology surrounding the sun is assured, it is necessary to validate the association between crabs and son gods. As Deonna, exposes on her study of animal symbolism, the correlation between the crab and the gods was common on coins and on monuments, and varied depending on the circumstance, ranging from river or sea gods to deities not connected with water, such as Apollo or Zeus.

In the case of Apollo, a god commonly associated with the sun, the correlations are uncertain, as, although Plutarch claims that Apollo “prefers anything to these shellfish,” numismatic and archaeological evidence provides several examples of this association, such as the coins of Croton or the head of Apollo at Cyrene. However, the connection appears to be not sufficiently popular to apply to our case-study. On the other hand, in Zeus’ case “the crab is often linked with Zeus or his attributes,” as visible through numerous archaeological artifacts and coins (such as Fig. 8). As the god is often associated with Ammon, this correlation appears more plausible. This connection was also synthesized by Warren, who writes that “the Roman ruler caused to rest the obelisk, symbol of Ammon-Generator, upon his attribute of Apollo—Egyptian and Roman signs together proclaiming to the world the awakening, the re-creative power of their god, the Sun, the re-creative power of the Divine toward all humanity.” Warren, therefore, views the Sun as the common denominator and, similarly, views the understanding of mythological parallelisms as an inspiration for political propaganda using a visual expression of power. This connection is a little frustrating, though, seeing as that by the Roman Period the fortunes of Amun (and Ammon) have plunged precipitously.

Fig. 8. Coin from Moitya expressing the connection between the eagle, symbol of Zeus, and the crab

The talisman theory

On the other hand, the talisman theory, which attributes to the crab apotropaic qualities, does not view the choice of sea-crabs iconography strictly as a political act but rather as a prophylactic decision, to hinder any evil eye. Moldenke contextualizes this idea within a tradition of the strange superstition of the Egyptians of the Ptolemaic period, claiming that the “figure of the scorpion, the evil genius, which played an important part in the astrological and mythological inscriptions of that time” had an apotropaic value. Moldenke also affirms that the Romans, however, rejected the scorpion iconography and instead embraced the figure of the crabs, because of its higher aesthetic value, judging the crab a more appropriate ornament for the obelisk. Archaeological evidence has, however, proven him wrong, revealing that the figure of the crab had already a predominant apotropaic role during Hellenistic time and in Ptolemaic Egypt. Starting with the Milatos’ vase, where the crab is included in a circle of protective animals who combat the influence of the evil eye, another extraordinary example is provided by the legend regarding the “glass, marble, and bronze crabs said to have been buried in the foundations of the lighthouse of Alexandria” in order to assure stability. This narration is invaluable as it provides an example of the use of crab-iconography local to Alexandria and in addition introduces the function of attributing stability in addition to talismanic protection. This topos of stability-providing crabs seems to have been manifest also in households, as revealed by another bronze crab, also part of the Metropolitan Museum collection (Fig. 9). In this case we see another naturalistic representation of a crab dating to the 3rd – 1st c. BCE, to be contextualized in Hellenistic culture. This crab has a hole at the top of the carapace and thus has been thought to have to have been placed as a furniture attachment or as a base, possibly for a lamp.

A combination of the two!

In exploring the different meanings of the crabs and comparing these two main hypothesis, ultimately it appears that all factors may be intertwined, reflecting the everlasting connection between the mythological iconography and power propaganda. The crabs thus come to exemplify and embody the spirit of Augustan Egypt, where not only symbols of power are reclaimed to reiterate new power dominion, but also where cultural syncretism serves the purpose of imperialism. This is best expressed by one last correlation between the sun and crab, manifested through the topos of the summer solstice. Constituting an extraordinary juncture between the sun symbolism theory and the talisman theory, this specific correlation between the crab of the Zodiac and the sun’s orbit has an influence on popular beliefs, as well as prophylaxis quality.

In Conclusion

In conclusion, the analysis of the two crabs and of their inscription, along with the study of the obelisk’s history, provides fascinating insight on the Roman rule of Alexandria and the development of the cult of Augustus in Egypt. The placement of the two obelisks in front of the Caesareum, and thus the place of cult of the emperor’s worship (the new temple to the sun, perhaps), reveals a sense of political continuity, expressed not only through the extension of the divinization of the king from the Old Kingdom up to Roman times, but also through the assimilation of local political imagery, such as the obelisk. Yet, contemporarily it reveals the profound political break that Egypt undergoes during Augustan times. The analysis spurred from the study of the two bronze crabs used as supports for “Cleopatra’s Needle,” is thus emblematic of the political and religious transformation that took place during Augustus’ rule of Alexandria.

Footnote [I copied and pasted this from a word doc and all the footnotes got lost. I didn’t have time to write out all by Sunday but will do it soon. As for the bibliography — I wanted to include it in a different pop up page]

1. Merriam, Augustus C. The Greek and Latin Inscriptions on the Obelisk-crab: In the Metropolitan Museum, New York: A Monograph. New York: Harper, 1884.

2. Ibid., 48.

3. Moldenke (1935:18)

4. Deonna (1954:53)

Transporting the Obelisk

As the only mobile and traveling monument of the ancient world, the obelisk becomes an emblem of religious and political power, and, especially in the case of the “Cleopatra’s Needles” one can retrace their metamorphosis through time, starting from the “overwriting” that took place during the pharaonic time (see Ramesses II writing over Thutmose III) to its actual transfer to new epicenters of power during the Roman period (see Alexandria and Rome). The two bronze crabs used as supports for “Cleopatra’s Needle” are, once again, emblematic of the political and religious transformation that took place during Augustus’ rule of Alexandria. The obelisks of Thutmose III and Ramesses II, symbols of the majesty of these great Egyptian conquerors were now balanced cautiously on four small bronze crabs of Hellenistic manufacture and Roman property; similarly Alexandria and all of Egypt was now in the power of the heterogenous Roman empire and its Caesar Augustus and cradle of Hellenistic creative endeavor.

Where the obelisks are located today [Here I would have included a list + a map]

The practice of placing bronze elements to support the transferred obelisks persisted beyond the Hellenistic time and is visible in several obelisks around the world. [Here I would have included images of the obelisk in Florence + in Istambul]